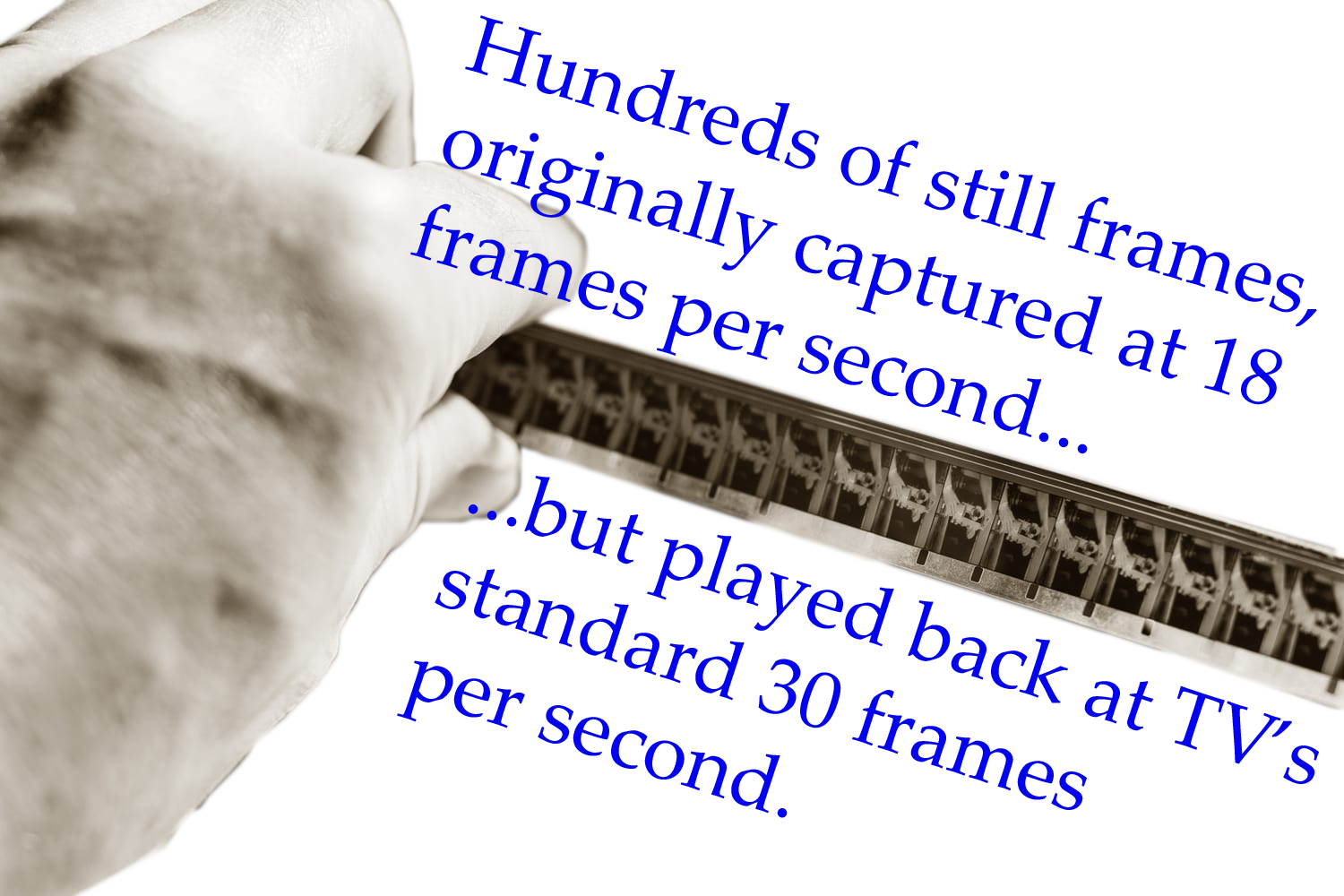

Home movie film, of course, is merely a collection of hundreds of still pictures taken about 55 milliseconds apart or 18 frames per second (fps). When played back at that same speed, there is an illusion of fluid motion-preserving for future viewers memories from that event where the film was taken.

Home movie film, of course, is merely a collection of hundreds of still pictures taken about 55 milliseconds apart or 18 frames per second (fps). When played back at that same speed, there is an illusion of fluid motion-preserving for future viewers memories from that event where the film was taken.

But home movie film is no longer used with the advent of mature video technology. So, the obvious question then emerges…how do you duplicate film to video? Video works on the same principle as film, which is creating the illusion of motion with a series of still pictures taken milliseconds apart. It should be simple as pie to duplicate home movie film into the digital domain for TV. However, there are complications that this article will explore.

To the consumer, it sounds like a perfect idea to just make a frame for frame duplication, but in practice, it doesn’t work out. For 24 fps Hollywood films (with massive budgets), among other things, they do what is called a 3:2 pull-down, which you can google for more information. This is adding a still frame every so often to make up for the time difference. For every 4 frames, copy the last frame. But after five groups of 4 frames, add a copy after only 3 frames. In doing this, movie film’s 24 frames per second becomes 30 frames per second which is compatible with the Northamerican television standard. This process is very labor intense but with a Hollywood blockbuster budget easily absorbed. But even with this there are problems in professional Hollywood film duplication to digital though they are minor and easily tolerated. It takes a trained eye to see the differences.

A similar process can be done to make 8mm home movies, captured at 18 fps, compatible with Northamerican TV. But do the math. With Hollywood films we were dealing with 24 fps so the ratio was 24/30. But what is 18 divided by 30? To meet the TV standard we are adding a frame copy more than every two frames! But unlike the 24 fps conversion, the problems resulting from this become noticeable to the untrained eye. I would describe it as a “lurchiness.” To the untrained eye this lurchiness will sadly be attributed to the limitations of home movie film.

But consider the implications when such a pull-down process is used. The studio time for the process is exorbitant driving the cost to process up markedly. But most consumers are not operating with a Hollywood budget so something has to give. It is only natural that service providers operating in this fashion will look for corners to cut. It is simply Marketing 101. Consequently, the best solution for a frame-by-frame process is to not do a pull-down and accept the result. The result is a Keystone Cops effect where we violate the gravitational constant of the earth. Children swinging at a playground look unnatural, people walking or running look weird. To quantify the effect, people are moving at 30/18ths (166%) of normal motion.

There is, however, an alternative to a pull-down solution. Rather than mess with a complicated process of adding periodic frames, the section can be transcoded to another format but with a playing length adjustment. For film originally captured at 18 fps, once captured frame-by-frame, it can be transcoded at a 60% time reduction. The digital duplication clip running 3 minutes in a frame-by-frame mode will now run for the original 5 minutes it used to run when the family viewed the projection on the wall back in 1960. But of course, it is obvious that the studio overhead has now doubled, radically reducing a net profit. To make matters worse, if the frame-by-frame capture was in a compressed mp4 format, the transcode of it will have artifacts.

When entrepreneurs think about how they can invent a telecine machine, they naturally think frame-by-frame. I see many systems on YouTube where this is what they have done. It really is a good idea from a marketing perspective because to the unaware it makes sense.

Let’s consider the cost of doing business. When capturing frame-by-frame, the time per foot of film is through the roof. Playing a 50-foot reel of film in real-time as we do is about a little less than 4 minutes. However, a frame-by-frame capture is a little bit more than one hour for a 50 foot 3-inch diameter reel.

There is another aspect to frame-by-frame to consider that is used often incorrectly for the purpose of appearing as high-quality. That is where film frames are “scanned” rather than “captured.” Consider the Wolverine conversion device. Reading the description you will see that film is “scanned” frame by frame. But reading further into the description we see that the “scanning” is by means of a video camera.

When I first saw the Wolverine device for sale I took it for what it said and thought that it might be an incredible device for me to use in my own film duplication business. But to understand what I am talking about, it is necessary to understand the differences between scanning and capture.

Scanning vs Capture:

In my business I duplicate 35mm color slide transparencies to digital. Except for the size, a color slide is exactly the same as one frame of 8mm home movie film. I will scan a 35mm color slide at 2400 dpi. A tiny 1 inch slide can then be blown up to poster size with sharp detail. But it takes about 4 minutes to scan a slide at 2400 dpi. First there is the image scan, then there is the infrared scan to map dust particles, and then a high-dynamic range scan to improve the dynamic range of the duplication.

What if we could scan each frame of a 50 foot 8mm home movie reel! Think of the incredible quality! But sadly, you can only get so much out of 8mm film but nevertheless, the quality would be noticeable. But what resources are required to do this trick? For the sake of simplicity, let us assume that each frame is 8mm in height. How many frames are on a 50 foot reel?

1 frame/8mm * 25.4mm/in * 12 in/ft * 50 ft = 1900 frames roughly

Let us then assume that one 8mm frame is only 20% of a 35mm transparancy. Scanning an 8mm frame should take about 50 seconds (but let’s call it 25 seconds).

1900 fr * 25 sec/fr * 1 min/60 sec * hr/60 min > 13 hours per reel

With a Hollywood Blockbuster budget there is money to pay for that duplication. And that is exactly what a “flying spot scanner” does. But it is clearly outside of the consumer market. Thus, the Wolverine simply does a video capture, but still, frame-by-frame. Certainly, the results are acceptable for the dedicated consumer.

I don’t want to be perceived as saying NOT to buy the Wolverine. It has a market for the dedicated consumer and will return acceptable results.

Practical Analysis:

Playing the film in real-time is 4 minutes, while a frame-by-frame capture is over an hour to complete (not scan) of the entire 50 foot reel.

What Does This Mean:

In frame-by-frame, the download must run unattended. What does THAT mean?

What if something goes wrong such as the film breaks. If the film breaks, it will spool out onto the floor if nobody is there to correct it. It’s okay to carefully handle movie film with your bare hands, but you CANNOT let it touch even a very clean floor where it will, in all cases, pick up massive, massive lint and dust particles. You can clean the film with special film cleaning agents, but the damage has been done and cannot be entirely corrected.

What if the film transport path loses its loop? If the film transport path somewhere loses a loop, then it is impossible for the projector to fully stop each frame for projection. The projection will be a mix of projected frames and unviewable. Worse, the projector film-advance claw will pull at the film, attempting to advance it, which will permanently distress the film in a minor way.

Because the film is not playing in real-time, a soundtrack cannot be captured during the download. For Hollywood films, they know with precision where the soundtrack is supposed to be so they can marry the soundtrack and digital image later. In a simplified frame-by-frame download, that precision does not exist. You could make an attempt to marry the two in post, but there would be severe annoying lip-sync problems.

The reader is encouraged to go to YouTube and search for “telecine” where the reader will find loads of these frame-by-frame configurations. It really is a good idea but not for home movie transfer.

Often times we are contacted by consumers looking for home movie transfer who ask about our process. As the reader may have surmised to this point, it is too complicated to explain. We end up sounding like we are trashing frame-by-frame when an honest simple look reveals the story. That is why we offer to do one reel for free (with a watermark) for comparison purposes. The proof really is in what you see, talk is cheap.